살 and 쌀 are the same word

In Ukrainian cats (кіт / kit) and whales (кит / kyt) are the same thing, if you ask my ears. As are being hungry (голодний / holodnyj) and cold (холодний / kholodnyj).

I can never know if their whale is hungry or if their cat feels cold.

I don’t get it. A little more context would be appreciated. Are they pronounced the same or mean the same or both?

They aren’t the same.

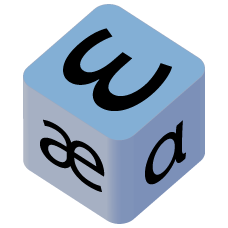

살 /sal/ “meat” is pronounced with [sʰ]. It’s roughly like the “ssh” in “grasshopper”.

쌀 /s͈al/ “uncooked rice” uses [s͈] instead. It’s a “tense” consonant; if I got it right the main difference is faucalised voice, you’re supposed to lower the larynx a bit while speaking it.

Since the difference yields different words, they’re a minimal pair so they aren’t allophones but different phonemes. If you speak Korean (I don’t) the difference between those two is on the same level as the one between English “bot” vs. “pot”, or between “bit” and “beet”. However since the contrast isn’t common out there they sound similar for non-speakers, and I think this to be what OP is trying to convey.

Oh it’s so hard sometimes to get these differences because one just… doesn’t get it. Doesn’t have experience of the difference.

In Finnish vowel length matters a lot, and when there are non-native speakers, it’s painfully obvious, as that’s something that’s hard to “get right” if you haven’t been exposed to the difference since you were a kid.

It’s probably a somewhat subjective feeling of mine, but I’m pretty sure it’s easier to pass as a native speaker of English to English native speakers than it would be to do the same for Finnish. Similarly I’d have a lot of trouble learning the tonal and other minor differences in lots of Asian languages as Finnish or English or any other language I speak doesn’t really utilise them as much. So I’m “deaf” to them. For now.

Yup - we train ourselves to ignore distinctions as “not meaningful” because of our native languages, and then when we learn another language, one that uses those distinctions, it bites us back. You can get it later on, mind you, but it’s always a bit of a pain.

My personal example of that is from Italian (L2): it took me a few years to be able to reliably distinguish pairs like “pena” (pity) and “penna” (feather), simply because Portuguese (L1) doesn’t care about consonant+vowel length.

My personal example of that is from Italian (L2): it took me a few years to be able to reliably distinguish pairs like “pena” (pity) and “penna” (feather), simply because Portuguese (L1) doesn’t care about consonant+vowel length.

I’d like to assume you changed the words of the mishap, and you we’re actually in a restaurant, and instead of ordering “penne arrabbiata”, you asked for an angry penis, “pene arrabbiata”.

Like Tuukka there in a reply above this pointed out, the vowel length in the word “tapaan sinut” and “tapan sinut” in Finnish is very important, as the first one is “i will meet you” and the second one is “I will kill you”. You can also change the consonants while having the same vowels if you just use the lemma of the word. “Tappaa” = to kill, “tapaa” = to meet

And a habit as in a custom, tradition, personal habit, would be “tapa”, which is actually a synonym for “kill” in imperative form.

I like to imagine how fucking hard it would be to learn Finnish and thank my lucky stars I’ll never have to.